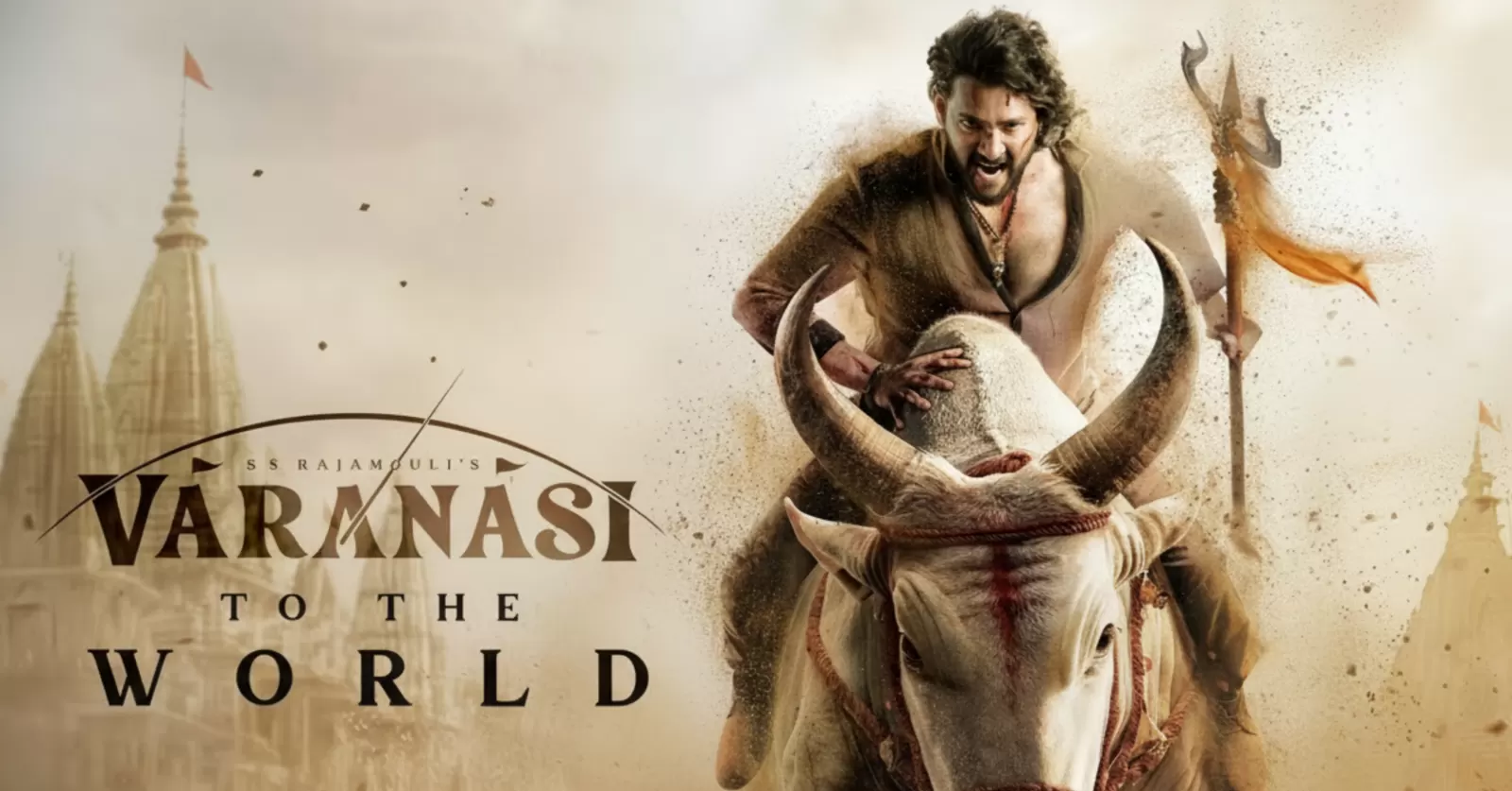

When the opening shot of Varanasi lingers on the river at dawn mist rising, boats slicing through a soft, orange light it doesn’t feel like a location mere filmmakers picked for looks. It feels like the film has arrived somewhere with a history, and it intends to listen. What follows is less a plot you can reduce to beats and more an accumulation of observations: characters who carry rituals as burdens, a city that acts like a character itself, and a story that keeps nudging us toward questions about faith, loss, and the slow work of atonement.

Not a sermon, but a pilgrimage

On the surface, the film is straightforward: a young man returns to his ancestral city after years away, tasked with settling a familial debt that’s as moral as it is monetary. On paper, this could have been a moralistic parable. Instead, the director treats the narrative like a pilgrimage. Scenes unfold at the pace of footsteps measured, irregular, sometimes stopped by the intensity of a moment or a face in a crowd.

During my screening, I noticed the film rarely tells us what to feel. It stages situations where belief and doubt collide and then steps back, letting the audience witness the friction. That restraint is the movie’s real strength. The spiritual isn’t spelled out in voiceover; it’s present in the cadence of everyday life in the way a character pauses before offering food to a stranger, or the awkward silence after a prayer that wasn’t returned.

Visual language as scripture

The cinematography reads like a text. Long takes track along ghats, following characters as if to remind us that history is made in small, repeated gestures. Close-ups are used sparingly, and when they arrive they feel like confessions: a tremor in a hand while holding incense, a lip pressed tight against regret. The river is photographed almost obsessively; sometimes placid, sometimes lined with the messiness of commerce and devotion. It functions as both mirror and margin reflecting the characters’ inner states and delineating where the city’s public performance of faith ends and private doubt begins.

Color is another language here. Earthy ochres and the saffron of robes pop against the concrete and grime, reminding us that sacredness and squalor coexist. The production design resists idealizing the city; it embraces its contradictions. That choice gives the film moral weight without moralizing.

Characters who are quietly complicated

The protagonist is a study in contradictions: pragmatic enough to negotiate with moneylenders, tender enough to linger over a child’s first steps. He returns with a suitcase of compromises and a face accustomed to compromise. The supporting cast is similarly textured. A woman who runs a tiny tea stall is both an oracle and a realist; a priest is neither wholly corrupt nor purely spiritual he’s human, and disappointingly, that’s more interesting.

What keeps these figures alive is the script’s refusal to turn them into symbols. They carry ritual, yes, but not all ritual is unambiguous. Some acts of devotion are sincere; others are performative, a currency exchanged to access networks, favors, or a sense of belonging. The film is keenly aware that a city’s religious life contains many economies spiritual, social, and economic that intersect and sometimes contradict.

On grief and reclamation

A thread running through the movie is grief: personal loss, generational loss, the loss of faith. The returning protagonist is haunted by an absence whose contours are revealed in domestic moments rather than monologues. The film stages grief like a landscape: rooms that smell of someone who is gone, a shirt folded just so, a single photograph left on a windowsill. These small details accumulate and deliver the emotional heft without a speech.

Reclamation, meanwhile, is not a single grand gesture but a series of small reparations returning an old debt, redistributing land, speaking truths that had been avoided. The film insists that salvation is rarely spectacular. It is meaner, humbler work: apologizing, listening, changing how you fold a sari, refusing to look away.

Faith under pressure

One of the movie’s more interesting choices is how it places faith under practical pressure. Rituals that once seemed timeless become negotiation tactics when a local factory closes, when water is diverted for private projects, or when a community decides that a shrine is worth selling. The film poses a difficult question: what happens to sacred practices when survival demands different priorities?

In scenes where priests haggle over the price of performing last rites, the film doesn't mock religion; it registers the absurdity and pain of seeing what was once beyond price assigned a cost. Those sequences are bracing because they refuse sentimentalism. They ask us whether faith is robust enough to survive commodification or whether it will mutate into something else, perhaps more pragmatic, perhaps thinner.

Ritual as conversation

Ritual in this movie functions not only as worship but as a form of dialogue. Characters use rites to speak across divides: a woman uses a small puja to communicate love, a young man lights a lamp to mark his resolve, elders sit in the shade sharing tea and warnings. The camera treats these moments as speech acts not performances for our benefit, but attempts to make meaning in community.

Ambiguity as ethical choice

What the film refuses to deliver is tidy closure. The ending is not a denouement where everything is explained, but a return to the everyday: people moving through the city, markets opening, the river flowing. That deliberate ambiguity is the film’s ethical choice. Life, the movie suggests, is rarely settled. Some harms are repaired; others remain. The moral work is ongoing.

By resisting the temptation to tie up loose ends, the director asks a larger question: what does it mean to live in a place shaped by ritual when the certainties that supported those rituals are eroding? The refusal to answer is not evasive; it’s faithful to the lived reality the film depicts.

Small moments that linger

- A scene of a small boy learning to swim, watched by elders who once feared the water. It becomes a metaphor for risk and courage.

- A late-night rooftop conversation where two characters trade stories of people they’ve lost the intimacy of the exchange is rendered without melodrama.

- An exchange of letters, read aloud in pieces, that reveals a history of choices made for survival rather than virtue.

Why it matters

On the surface, the film is a localized story about a specific city and its people. But its concerns are larger: how communities negotiate meaning when old structures falter; how devotion survives in economies that prize speed and utility; how individuals seek repair in places shaped by both the sacred and the profane. That universality is what the film’s makers have gently pursued: the particular leading to the universal, not by sermonizing but by attending to texture.

From what I observed, the movie’s real ambition is quieter than declaration. It wants viewers to sit with the unease that comes when rituals can't fully protect us from the pressures of modern life. It wants us to recognize the dignity in small acts of faith, the possibility of moral repair, and the stubbornness of everyday life.

A final image

The last shot lingers on the river again, but now at dusk. Lamps float by, some bright, some sputtering, some blown out. People stand on the bank, some joined in conversation, others alone with their memories. There is no final answer. There is motion water, wind, human breath. The film trusts that this motion is enough: that meaning is not a trophy we win at the end but the practice we return to, imperfectly, day after day.

For viewers willing to slow down and listen, the movie offers small consolations rather than certainties: the possibility that ritual can be reimagined, that grief can be tended, and that living in a sacred city is as much about negotiation as it is about devotion. It’s a film that asks us to pay attention not to find a single truth, but to sit with many, and to let them complicate how we live next.